I am often asked about nightshades and nightshades have a reputation as the bad guys in a variety of chronic conditions, such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, and IBS. Should you eat the deadly nightshades? What do we really know about how these foods affect our health?

What are nightshades?

Nightshades are a term commonly used for the group of plants in the Solanaceae family.

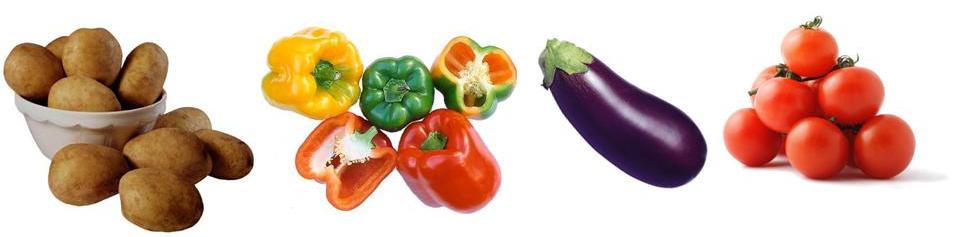

You will find quite a wide range of edibles in this family, as well as several poisonous inedibles. Tasty and familiar edibles such as tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, red, green and chili peppers as well as paprika and tomatillos and the tobacco plant are all nightshades. Even the popular and celebrated superfood, goji berries are in this family.

Meet the Nightshade (Solanaceae) Family:

- Potatoes

- Tomatoes

- Peppers

- Eggplant

- Tobacco

- Golgi Berries

Nightshades of all types were considered inedible prior to the 1800’s, because some varieties, such as “deadly nightshade” (atropa belladonna) were known to be so incredible toxic. History tells us that plants from the nightshade family, like datura and mandrake were commonly used for many centuries as sedatives, hallucinogens and truth serums However, today most Americans eat “edible” nightshades every day in the form of French fries, mashed potatoes, salsa, spaghetti sauce, ketchup, and many other popular foods.

What is it that makes these plants so potent?

Both the medicinal and the toxic aspects of nightshades can be attributed to their glycoalkaloid properties.

What are glycoalkaloids?

Glycoalkaloids are natural pesticides produced by nightshade plants. They are bitter compounds which are found throughout the plant, but especially in leaves, flowers, and unripe fruits. They defend the plants against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and insects.

How do these chemicals kill pests? All plants come with a built-in defense mechanism to defend themselves against predators, because unlike animals, plants can’t run away. No kidding! I think it’s only fair, porcupines get big spikes, cheetahs can run fast, bears are big and scary, and plants needed a defense mechanism too – they got phytochemicals.

Phytochemicals are naturally occurring, chemical compounds found in plants and there is a huge range of them, with alkaloids being only one category of phytochemicals. Plants want to keep their plant species alive, just like animals do. So when they are in danger of being eaten they create these plant chemicals or alkaloids, in small amounts to protect themselves. The plant starts to taste more bitter, and the ‘predator’ (whether animal, human or insect) stops eating it. Plants are so intelligent that when one plant starts to get eaten, it increases the production of alkaloids and that chemical actually signals the other plants nearby to start making this same chemical as well, to protect itself from the danger of being completely eaten – pretty amazing, wouldn’t you say?

Glycoalkaloids bind strongly to the cholesterol in the cell membranes of predators, disrupting the structure of their membranes, and causing their cells to leak or burst open upon contact—acting like invisible hand grenades.

Ever wonder why you have always heard that you can’t eat sprouted potatoes? That’s because the glycoalkaloid content is considerably denser in the sprouted areas, and can be harmful. The concentration can actually be up to four times more intense if the potato was stored in the light, which is why potatoes should always be stored in a cool, dark place. Ever gone to ‘peel the spuds’ and you see they are green? Strangely, that green is not the poison itself but chlorophyll, which is harmless. The green color is, however, a good indicator that that part of the potato may contain higher levels of poisonous compounds.

Glycoalkaloids have another powerful trick up their sleeves—they also act as neurotoxins, by blocking the enzyme cholinesterase. This enzyme is responsible for breaking down acetylcholine, a vital neurotransmitter that carries signals between nerve cells and muscle cells. When the enzyme is blocked, acetylcholine can accumulate and electrically overstimulate the predator’s muscle cells. This can lead to paralysis, convulsions, respiratory arrest, and death. Military “nerve gases” work exactly the same way. Ok, so glycoalkaloids are clearly great defensive compounds used on tiny critters that dare try and eat the plant. But how much do we know about their effects on human health?

Proposed glycoalkaloid health benefits

Health benefits? From a pesticide? Hmmm…

Glycoalkaloids are structurally similar to glucocorticoids, such as our body’s stress hormone, cortisol. Cortisol has many roles in the body, one of which is to reduce inflammation. Therefore, perhaps it is not so surprising that glycoalkaloids have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties in laboratory studies of animals.

It should also not be surprising that glycoalkaloids have been shown in laboratory studies to possess antibiotic and antiviral properties, since this is what nature designed them for.

In laboratory (in vitro) studies, glycoalkaloids can trigger cancer cells to self-destruct. This process is called “apoptosis.” Unfortunately, they can also cause healthy non-cancerous cells to do the same thing. Cancer studies in live animals and humans (in vivo) have not yet been conducted.

The other side of the coin!

Research has shown that glycoalkaloids can burst open the membranes of red blood cells and mitochondria (our cells’ energy generators). Some scientists have wondered whether glycoalkaloids could be one potential cause for “leaky gut” syndromes due to their ability to poke holes in cells. Glycoalkaloids are also known to cause birth defects in laboratory animals.

Potato glycoalkaloids

Nightshade potatoes include all potatoes except for sweet potatoes and yams.

Potatoes make up the two most toxic glycoalkaloids found in the edible nightshade family. Most of us do not associate potatoes with illness, probably because the amount of glycoalkaloid most of us eat every day is not very high. There are numerous cases of livestock deaths from eating raw potatoes, potato berries, and potato leaves, but people do not eat these things. However, there are well-documented reports of people getting glycoalkaloid poisoning from potatoes, typically from eating improperly stored, green, or sprouting potatoes. At low doses, humans can experience gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting and diarrhea.

At higher doses, much more serious symptoms can occur, including fever, low blood pressure, confusion, and other neurological problems. At very high doses, glycoalkaloids are fatal. Another reason why many people may not be bothered by potatoes is that glycoalkaloids are very poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, so, if you have a healthy digestive tract, most of the

glycoalkaloid won’t make it into your bloodstream. However, if you eat potatoes every day, levels can build up over time and accumulate in the body’s tissues and organs, because it takes many days for them to be cleared. Also, since glycoalkaloids have the ability to burst cells open, they can theoretically cause damage to the cells that line your digestive system as they are passing through.

The FDA limits the glycoalkaloid content in potatoes to a maximum of 200 mg/kg potatoes (91 mg per pound). Human studies show that doses as low as 1 mg glycoalkaloid per kg body weight can be toxic, and that doses as low as 3 mg/kg can be fatal. This means that, if you weigh 150 lbs, then doses as low as 68 mg could be toxic, and doses as low as 202 mg could be fatal.

Potato processing 101

The vast majority of glycoalkaloid is in the potato skin, so peeling will remove virtually all of it. Glycoalkaloid levels can be dangerously high in unripe and sprouting potatoes; any greenish areas or “eyes” should be removed or avoided.

Glycoalkaloids survive most types of cooking and processing. In fact, deep frying will increase levels if the oil isn’t changed frequently, so fried products such as potato skins and french fries can contain relatively high amounts:

Tomato glycoalkaloids

Tomato nightshades include all types of tomatoes: cherry tomatoes, green tomatoes, yellow tomatoes and ripe red tomatoes.

Tomatoes produce two glycoalkaloids and they are about 20 times less toxic than potato glycoalkaloids. Green tomatoes contain more glycoalkaloids that red and ripened tomoatoes.

Eggplant glycoalkaloids

Known as an aubergine in my home country, centuries ago, the common eggplant was referred to as “mad apple” due to belief that eating it regularly would cause mental illness. Eggplants produce two glycoalkaloids both pretty potent. Whereas potato glycoalkaloids are located mainly in the skin, in eggplants, glycoalkaloids are found primarily within the seeds and flesh; the peel contains negligible amounts.

Nightshades and Nicotine

Nightshade foods also contain small amounts of nicotine, especially when unripe. Nicotine is much higher in tobacco leaves, of course. Scientists think that nicotine is a natural plant pesticide, although it is unclear exactly how it works to protect plants from invaders. The amount of nicotine in ripe nightshade foods ranges from 2 to 7micrograms per kg of food. Nicotine is heat-stable, therefore, it is found in prepared foods such as ketchup and French fries. The health effects of these small doses is not known, but some scientists wonder whether the nicotine content of these foods

is why some people describe feeling addicted to them.

Do you have nightshade sensitivity?

As with any food sensitivity, the only way to find out is to remove nightshades from your diet for a couple of weeks or so to see if you feel better. There are ZERO scientific articles about nightshade sensitivity, chronic pain, or arthritis in the literature, however, the internet is full of anecdotal reports of people who have found that nightshades aggravate arthritis, fibromyalgia, or other chronic pain syndromes. I personally am very sensitive to nightshades; they cause me a variety of symptoms, most notably heartburn, difficulty concentrating, pounding heart, muscle/nerve/joint pain, and profound insomnia. Everyone is different, so as always, you’ll need to discover for yourself whether these foods may pose problems for your individual dosha or metabolic type. It does seem that Vatas and Pittas tend to be more sensitive to the nightshade family. However, given what we know about nightshade chemicals, common sense tells us that these foods are well worth exploring as potential culprits in pain syndromes, gastrointestinal syndromes, and neurologic/psychiatric symptoms.

So Are They Ok to Eat or Not?

There is not a one-size-fits all answer to this question, but there are a few issues that are widely exacerbated by nightshades. If you have one of the following issues, I would recommend eliminating nightshades:

- Autoimmune diseases

- Arthritis

- Gout

- Osteoporosis

- Ongoing inflammation

- Rheumatoid arthritis

The edible members of the nightshade family tend to be very nutritious and are often staples in the food plans of certain cultures, but it is still possible to have a bad reaction to them. If you experience bad reactions like stomach pain, nausea or flushing, you may want to try avoiding nightshade vegetables if you have a history of bone or joint problems, like rheumatoid arthritis.

While we know that vitamin D is essential for healthy bone formation, there has been some animal research suggesting that the vitamin D in nightshades may cause calcium to be deposited in the wrong places in the body, like soft tissue and kidneys, instead of in the bones where it belongs.

How to eat nightshades

If nightshades are not a sensitivity for you and they do not cause unpleasant symptoms for you, here are some tips to enjoy nightshades in your diet:

· Choose ripe nightshades, since solanine levels are highest in unripe ones. For example, choose juicy red tomatoes over green tomatoes and red peppers over green peppers.

· Cook nightshades if practical, since cooking reduces alkaloid content up to 50%. Lectins are also degraded, to varying levels, with cooking.

· Use moderation and variety. I don’t think that anything should be eaten everyday, because that can cause the body to develop a sensitivity. So it isn’t a great choice to use tomato sauce and ketchup as a daily condiment. Enjoy variety in your meals and that will help you eat nightshades in moderation.

Not sure if nightshades are right for you? Sign up for a complimentary consultation today to discuss what works best for your metabolic body type.